The paper in Nature Ecology & Evolution is here: http://go.nature.com/2wkLOrl

The Cambrian Explosion, when most major animal groups suddenly appeared in the fossil record, remains one of the most enigmatic events in evolutionary history. This event is best represented by a few exceptionally well-preserved fossil assemblages from around the world. The Chengjiang Biota from Yunnan Province, Southwest China, records a diverse range of extraordinarily preserved animal fossils dated around 520 million year ago, representing the earliest record of a complex ‘animal-rich’ marine ecosystem and a unique window into the structure of early Cambrian communities. Since the discovery of the Chengjiang Biota in 1984 by my former supervisor Prof. Xianguang Hou, over 200 animal species across 16 phyla have been reported from this World Heritage Site and it continues to bring us surprises. Among those early residents on Earth, worms mattered.

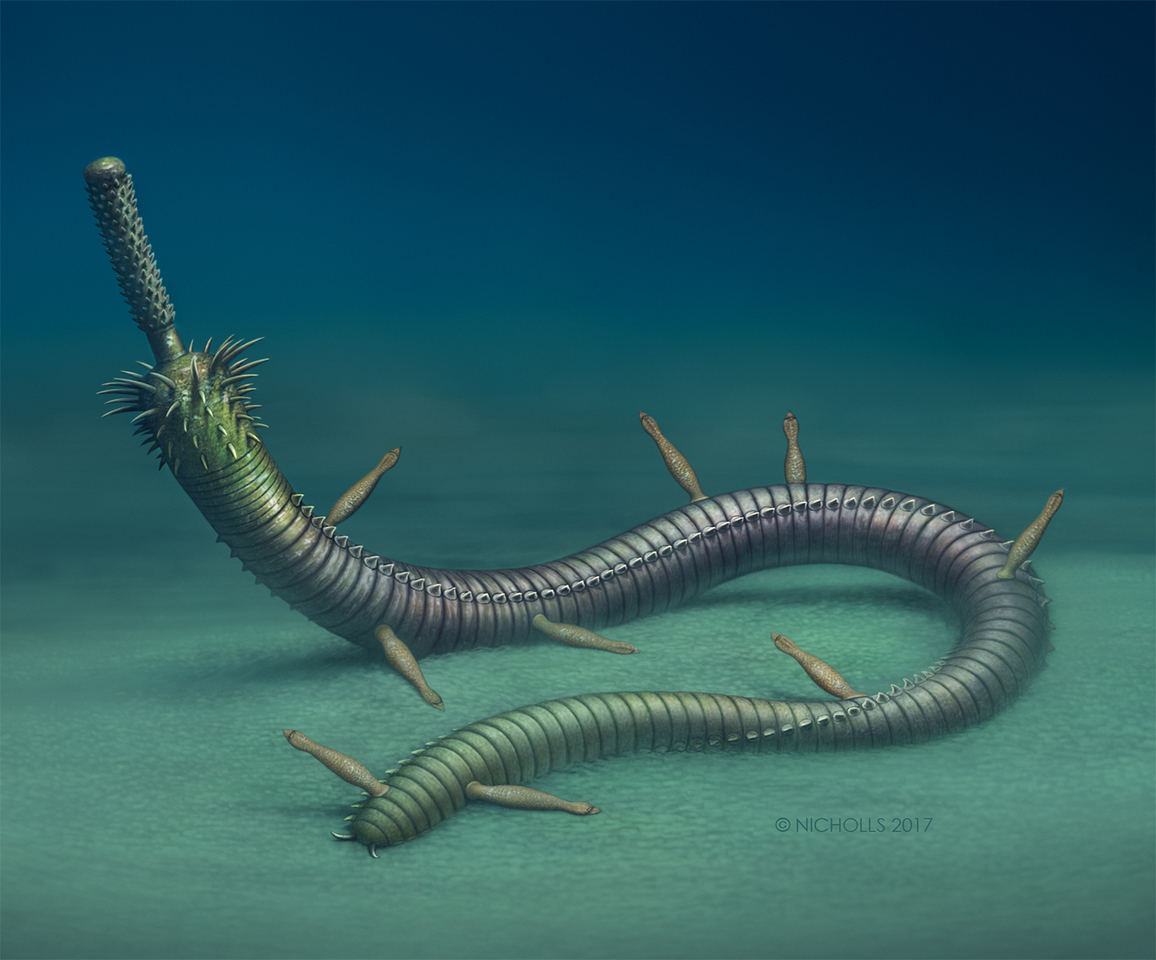

In the Chengjiang Biota, there are over 50 species of worms (short and long, thin and fat, spiny and smooth, etc.) together with the arthropods dominating the community, both in terms of quantity of individuals and diversity of taxa. Most of these worms are related to the phylum Priapulida, which has only 19 species today and are commonly known as penis worms. Cricocosmia jinningensis and Mafangscolex sinensis are two of the most common priapulid-related worms in the Chengjiang Biota, with thousands of specimens being collected.

Twelve years ago, I started my PhD project with Professors David Siveter and Sarah Gabbott at the University of Leicester (UoL) on “Vermiform Animals from the Lower Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerstätte”. In the course of this project, I carefully examined the worm collections at the Yunnan Key Laboratory for Palaeobiology (YKLP) in Yunnan University. Among nearly 3500 specimens of C. jinningensis and M. sinensis, a couple of specimens attracted my attention, as I could see some objects protruding from their elongated bodies. Despite piquing my curiosity, I was already occupied by other projects, and therefore these specimens were pushed to one side. In 2011, a couple more specimens were discovered when I started my postdoc research at the Natural History Museum in London (NHM). During the preliminary study, my colleague Prof. Greg Edgecombe and I thought that those protruding objects were outgrowths from the bodies of C. jinningensis and M. sinensis. This thought excited us, as it could mean that they represented a prototype of appendages and thus could fill in some missing links in animal evolution. However, something didn’t smell quite right, so we waited to see if any new specimens came to light.

Two years later, my colleague Prof. Peiyun Cong at YKLP collected an exceptionally well preserved C. jinningensis specimen with numerous objects attached to its curled and elongated body. Due to the amount of detail visible in this marvellous specimen, the penny finally dropped and the link with the earlier specimens became clear. It turns out that these small protruding, bowling-pin shaped objects are not body outgrowths of C. jinningensis and M. sinensis, but an independent and totally new species of worm, which we named Inquicus fellatus gen. et sp. nov. Two more host specimens were later collected by Dr. Dayou Zhai of YKLP that added to this research.

However, this is not the end of the puzzle, but rather a new ‘can of worms’ had just been opened. A series of questions were soon being asked: What are these little worms? What is the relationship between I. fellatus and their hosts? Why and how did they attach to the larger worms? With a joint effort across several institutions, many colleagues brought their expertise and experience into this study in order to address these questions. With the help of electron and confocal microscopist Dr. Tomasz Goral at the NHM, we threw every possible method at these fossil specimens, in the hope of extracting as much information as possible. A discussion and paper writing meeting was held at the YKLP late last year with Professors Mark Williams and David Siveter of UoL and Prof. Derek Siveter of Oxford University, and subsequently ideas were bounced around between the authors. The question was raised if it were possible that the little worms were actually the offspring of C. jinningensis and M. sinensis, but this possibility was quickly dismissed, as the little worms are identical across the two different host species and they have no shared characteristics with either the host worms or larvae typical of this group. Therefore, it was soon decided that we were looking at an early example of symbiosis.

We then considered that I. fellatus might be parasitic on the larger worms, which is still the opinion of Prof. Cong. However, the oral end of I. fellatus actually faces away from the host, their attachment discs do not penetrate through the hosts’ cuticle, and there is no clear evidence that the host worms were harmed because of this association. At the same time, failing to see how the larger worms benefit from this type of association, the relationship between I. fellatus and its hosts may have been commensal. After comparison with modern settings, we came to the conclusion that this is the earliest example of host specificity and host shift, as I. fellatus only infested C. jinningensis and M. sinensis from amongst over 50 species of worms in the Chengjiang marine communities.

After careful study, including much labour with the camera lucida to document the animals in precise detail, we presented our compelling case of symbiosis with the earliest evidence of aggregate infestation, host specificity and host shift to Nature Ecology & Evolution. Although there are still many questions remaining, such as the exact taxonomic affinity of I. fellatus (sharing some characters with rotifers and gastrotrichs, but also differing from both) and how/why it infests these larger worms, this study fills an important gap in our knowledge of the complexity of Cambrian ecosystems. Compared with more traditional palaeontological research, we hope this study will inspire further discussion about ecological as well as taxonomic diversification during the Cambrian Explosion.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in