My research for the past two decades has largely focussed on aliens (species introduced by humans to areas where they don’t naturally occur), and mainly birds. Birds were a good group to focus on because a catalogue of known bird introductions had been published in the 1980s, providing the data for numerous analyses of the characteristics of successful (and failed) aliens. However, in the mid noughties, I realised that a lot of bird introductions had happened since the 1980s, and that a new catalogue might be in order. I managed to obtain some funding for the project from the Leverhulme Trust, and in 2009 employed Ellie Dyer to do the actual work. She discovered that there are far more new introductions than I’d realised, and in the end spent seven years compiling the database, and analysing it for her doctoral thesis.

One of the key analyses I had hoped might be possible with the new database was an analysis of the causes of alien bird establishment success worldwide. However, this is a fiendishly difficult question to answer properly, because it involves combining information on the traits of species, features of the individual introduction (especially founding population size), and characteristics of the introduction location. The location is particularly hard to include properly in this kind of study - so many elements of it might matter to an arriving alien. For example, the climate is likely to be important, not just in absolute terms, but in how well it matches what the alien is used to back home. Which species are already present at the location is also likely to matter. Again, the identity of the alien matters in these regards – lots of similar species is likely to mean lots of competition with the alien, no similar species may be because the environment is not suitable for species like the alien. Habitat will matter, as will the extent to which humans have modified it. Finally, all of these features of the location vary over space and time in a non-random way, which introduces a range of analytical complications.

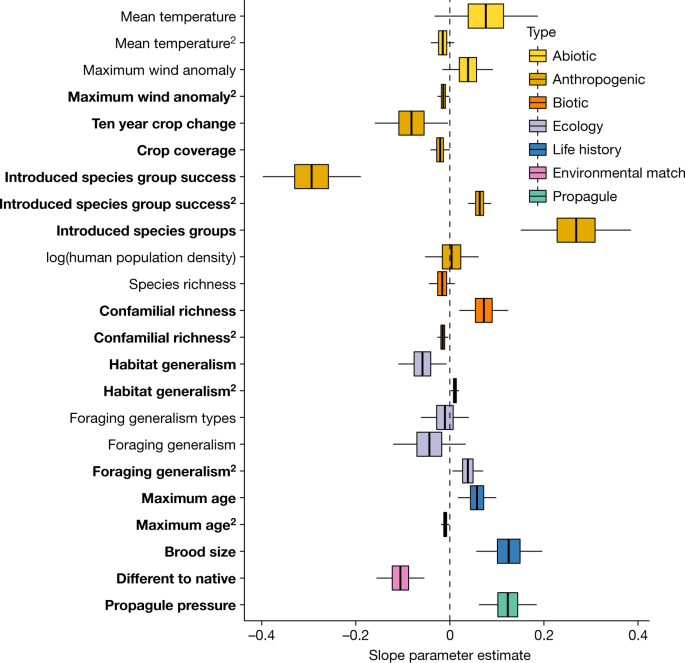

I’d more or less given up hope that this analysis might even be possible until Dave Redding arrived as a postdoc in my group. He worked with Ellie, further aided and abetted by Alex Pigot,Çağan Şekercioğlu and Salit Kark, to overlay her catalogue (> 4,000 alien bird introductions) with a mass of additional information. Dave chased down information on the climate, weather and other native and alien species present at the introduction locations. He calculated the climate match for every introduced species (more than 700) at every location of introduction, assembled data on the traits of the introduced birds, and their position in the bird phylogeny (and the relative positions of the birds already living at the introduction locations). Dave then applied state of the art statistical methods to assess the impacts of all these factors while accounting for the fact that features of locations and species are not independent.

You can read about the results of this big analysis by following the link above. The take home message is that features of the environment explained most variation in alien bird establishment success, but species traits and founding population size are also important. The most important environmental features were human impacts on the environment, and how well the new environment matched what the species was used to from its native range. Alien birds are more likely to establish populations in areas that already have more aliens of other sorts established there, consistent with the “invasion meltdown” hypothesis that previous invasions help future alien arrivals. If these results apply to more than just birds, they suggest causes to worry: ever more alien species are being introduced to new locations and getting the chance to test their environmental matches. Increasingly, the future is looking alien.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in